Nagurski also icon for family, hometown

The wet, low land near the Van Lynn Road produced bountiful blueberries. They provided the fruit for Michelina Nagurski’s blueberry jam sandwiches. She sent them everyday with her son Bronislau, as he left on foot for school in the Holler area. The trek through the fields and forests was four miles one way from the family farm.

Known as Bronko, the farm was his universe when the football world came calling. And then, unpredictable by anyone in the Ukrainian family, his brute strength and deft coordination would make him an indelible icon for pre-modern football and wrestling.

This farm boy would become the stuff of legends. It is often told that Bronko Nagurski was discovered by Minnesota Gopher coach Doc Spears while Bronko was plowing those farm fields — without a horse — and the coach asked in which direction the town was located. Bronko, as the story goes, silently aimed his plow at the distance.

A lot has been written about Bronko Nagurski — including Jim Dent’s 2003 acclaimed book entitled “Monster of the Midway.” And apocryphal tales always surface in the recounting of the legend. But the accounts of Bronko’s unprecedented athletic ability, his heroic humility and his love of Borderland are just the clean and simple truth.

Bronko Nagurski was born on Nov. 3, 1908, to Ukrainian immigrants Michael and Michelina in Rainy River, Ontario. He had two sisters, Stephanie and Eugenia and one brother, Marion. The patriarch worked the Rainy River railroads until he moved his family in 1912 to the farm in International Falls, where the promise of industrial expansion had been advertised by E.W. Backus.

With the ethics of the old-country, there was little time for anything but work. Mike logged off his Van Lynn property and milled the lumber for his 240-acre farm as well as other construction in the area. His farm and animals provided commodities for the grocery market he opened, called Nagurski’s. The corner store was near the home at 400 Eighth Street in the Falls (which still stands) where the couple would eventually retire.

These two from the Polish Ukraine could not have guessed that their shy, handsome son, who would own the farm himself until 1957, would become like Paul Bunyan — an American legend. He would make football history for “Papa” George Halas’ Chicago Bears while at the same time earn world titles in wrestling.

He could have made movies, wrote books, made appearances; but instead he wed his hometown sweetheart Eileen Kane in 1936, to raise six children in the Falls. In birth order, they are: Bronko Jr. who was born on Christmas day 1937, Tony, Janice (Carlson), Ron, Eugenia (Jauma), and Kevin.

Several of them spoke with The Daily Journal about Bronko the father, the man behind the legend.

Father

Son Bronko Jr. made his own claims in football as an All-Star playing nine seasons with the Hamilton Tiger-Cats, as well as for Notre Dame in 1956-58. Living in the legend’s shadow was inevitable because he carried the same name, he said. The press could never get enough of his father.

Although Bronko Sr. was a reticent man, he knew the art of skillful communication. Bronko Jr. remembers an instance at home after a Falls High football game in which he thought he’d played pretty well. However, his father noted a flaw.

“My dad told me that I wasn’t balanced in one stance,” said Bronko, Jr. “But I was cocky and told him he was wrong.”

To better make his point, the father had the son get back into position and asked if he was ready. In seconds, the sounds of the high-schooler crashing into French doors brought mother Eileen running from the other room.

But it wasn’t all football at their house, according to Bronko’s middle child, Janice Carlson. Athletics was not a priority.

“You better make sure your homework and your chores were done before you ran off to any games,” Janice said. While it is little known, Janice said that Bronko was actually credits shy of a degree at the University of Minnesota when pro football’s salary called him away.

But playing in the depression and WWII era, before football was the lucrative sport that it became, put education back in front. “We knew from the cradle that we were going to college,” said Janice, who was endearingly called “Stupendous” by her father. Janice said the sons and daughters were treated the same in a home where discipline was strict and her father backed her mother 100 percent. “We were expected to cook, do dishes, shovel snow and share the work.”

She said her father reflected an era of authority as well: “My father never argued our case. The teacher, the coach, the other child’s parent — was always right,” she said as she laughed.

But he was the gentle giant, said youngest son Kevin Nagurski. “In spite of the way he played ball, I don’t think I even got spanked,” Kevin said. “That was his game face.”

Behind the game face

Kevin recognizes that family dynamics naturally changed as the athlete returned to a simpler pace, buying the hometown Pure Oil Service Station in 1960 at 217 Third Avenue. Kevin remembers pumping gas in a place where his dad was content.

“My father traveled all over but he was never impressed with city life,” said Kevin. “That was work, wrestling was a job.”

Though pro-wrestling in the 30s was more respectable, Bronko likely did it to supplement his salary. His father hated wrestling’s showy antics, according to Bronko Jr.

“He shied away from the limelight and the notoriety that came with it,” he said.

Sometimes, he was awestruck by his own fame, according to Kevin. “He was amazed to be flipping the coin at the 1984 Super Bowl,”

Kevin said of Bronko’s last public appearance. “He gave a rare press conference for all the top reporters. They gave him a rare standing ovation.”

But once, Bronko’s fellow football star Leo Nomellini of the San Francisco 49ers misjudged Bronko’s humility. Bronko Jr. explained that his father did a lot of traveling during his wrestling tenure but didn’t have a huge wardrobe. A box from Nomellini arrived one day with a note saying that the nice suit inside was worn a few times but would probably fit Bronko should he like to keep it.

“Now, my Dad was ticked but he didn’t show it,” said Bronko Jr. Instead, he penned this reply to Nomellini: “Dear Leo: Thank you very much for the suit. But it doesn’t fit. It’s too small in the shoulders and too big in the ass.”

Behind the fame

It could have been the bonds of heritage; it could have been simplicity, but Bronko felt freedom in his hometown.

Bronko would take his children and visit his aging parents every single day, according to Janice. “He would go upstairs and speak Ukrainian with his bedridden father. We would watch their television because our family’s house was one of the last to get one.”

Bronko’s closest local friends were dentist Earl Milroy, Harold Kerry and Roy Manley. Hunting and fishing at a 1930s cabin on the lake and raising his family was really what he was all about, according to Kevin.

The nation continued to remember Bronko in mythical proportions: the frontier football man with an untamed force on the field. Reporters came and went; some wrote that Bronko was reclusive, embarrassed about aging and preferring to be remembered as the sinewy, vigorous athlete.

Shunning the cameras, he didn’t show for a Holiday Inn room dedication or a family event staged in his honor. Perhaps living up to the legend was a weary task for such a fundamental man. After his death, his life was honored by his city with the Bronko Nagurski Museum. The trophies, travels, images, artifacts and proclamations belie the soft-spoken older man who ran the gas station

locally. Bronko lived out his final years at the local nursing home where he stopped signing autographs due to arthritic hands. Years of the cracking tumbles had taken their toll. He reportedly loved to sing his fraternity song.

He died on Jan. 7, 1990, at the age of 81 and is buried in Forest Hill Cemetery in International Falls, the only place of all the places he’d been that he ever wanted to call “home.”

Living with the legacy

Six children, 15 grandchildren and five great-grandchildren go forward connected to a name that carries phenomenal recognition. Bronko Jr. and wife Beverly hope young people will visit the museum to see the meaning of Bronko Nagurski.

Janice says she generally hides from interviews. Like the father, all Bronko’s children are reluctant to boast. But there have been opportunities over the years to attend impressive events and meet extraordinary people.

“We met a lot of old players,” said Bronko Jr. “I met Red Grange and I have a pair of Jack Dempsey autographed boxing gloves.”

But their childhoods never really realized the extent of Bronko’s phenomenal fame.

“He was proud of International Falls and Minnesota,” said Kevin. “He was never interested in leaving.”

Bronko Jr. said that the material things and the fame weren’t important. “He always wanted to get back home,” he said. “He was a supporting father — a great father, really. He taught us all the things that fathers around here teach their sons. We didn’t see him as a legend — he was just ‘dad’.”

Bronko Nagurski The Legend

Bronko Nagurski has been chosen for the “MN 150 Exhibit” as one of 150 people or things that shaped Minnesota history. See this edition’s Leisure Page 1B, for the complete list and more on the Minnesota Historical Society exhibit.

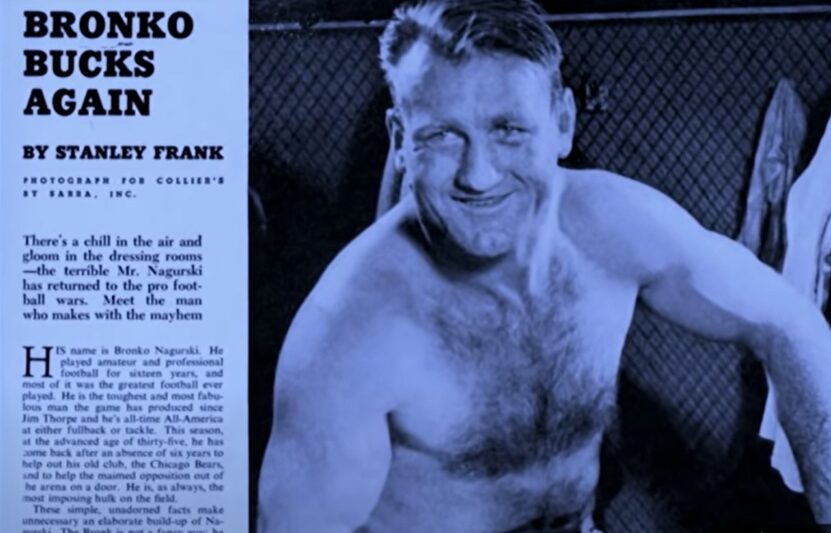

Bronko Nagurski’s strength is always described as super-human. At 6’ 2” and 225 pounds, he broke more opponents’ bones legitimately than any other player. In mythological descriptions, most who played against him said he was the most intimidating player of all time.

His body was large in his era for a lineman, unheard of in running backs. With an enormous neck and hands, his hallmark was raw power. He wore a record NFL ring size of 19.5 and helmet size 8. He had crowds on their feet at the age of 50 when he played in a 1958 Chicago Bears alumni game.

Among his honors:

•College football: University of Minnesota Gophers, 1927-1929.

Only collegiate player ever to be named a consensus All-American in same year at two positions: offense fullback and defense tackle

•All-Big Ten Championship 1929

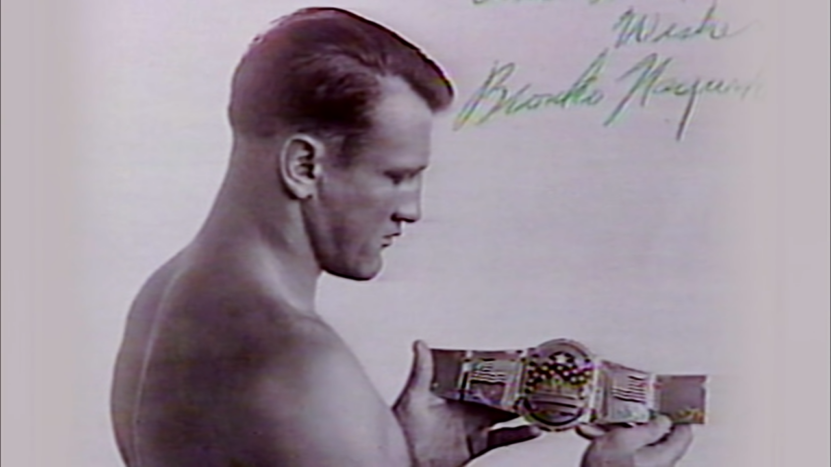

•Professional football: Chicago Bears, 1930-1937; Running over 4,000 yards with three NFL Championships, 1932, ’33, ’43. An astounding display in a 1943 comeback at age 35 is dramatized in the film “Hearts in Atlantis.” Only player in NFL history to be named All -Pro at three non-kicking positions: tackle, linebacker and fullback

•Professional wrestler: 1935-1958. Three-time World Champion 1937, ’39, ’41

•Charter member College Football Hall of Fame 1951

•Charter member Pro Football Hall of Fame 1963

•Ranked No. 2 greatest sportsman in Minnesota, second only to Kirby Puckett

•Minnesotan of the Year 1978

•Featured on 37-cent United States postage stamp

•Bronko Nagurski Legends Award goes to best college football defensive players annually

•Madsen’s All-Millennium Team 1999

•Written about in: “Monster of the Midway” by Jim Dent; “The Truly

Great” by Rick Korch; “Fifty Faces of Football” by Harold Rosenthal “The Great Running Backs” by George Sullivan; and numerous magazines and newspapers